Micro Design Systems

Breaking the Monolith

This article explores micro design systems as an alternative to monolithic ones. It suggests dividing design systems into modular, purpose-driven services, akin to microservices in software development, to accommodate growing design teams and products. These services include Core (foundational elements), Extensions (components that extend Core elements), and Frameworks (collections of elements with a common purpose). This approach offers flexibility, quicker design iterations, and improved scalability, although it does introduce some complexity and necessitates diligent maintenance.

Designers and developers love to imagine a single source of truth. A singular, universal solution that forms the foundation of everything we do. A pervasive, all-encompassing system.

A design system.

But, is that centralized, monolithic approach to structuring and documenting all things design the best way to go? I’m not sold on it.

Sure, structuring a design system as a one-size-fits-all repository sounds wonderful. And it might work out at first, but our teams will likely continue to expand. As our products grow, the number of designers working on them rises. And soon enough there’s a dozen — or several dozen — designers working on the same system.

And that’s when this monolith starts to crack, crumbling under the ever-increasing size of the design system. With every use case added or design pattern documented, its glamorous facade starts to fade.

Microservices for designers

In recent years, the microservice has picked up a tremendous amount of momentum. Touted by large-scale, complex services such as Uber, Netflix, and Amazon as the best way to tackle the complexity of scaling system architecture, it’s easy to see where its popularity stems from.

For those unfamiliar with the term, Amazon describes microservices as follows:

Microservices are an architectural and organizational approach to software development where software is composed of small independent services that communicate over well-defined APIs. […] Microservices architectures make applications easier to scale and faster to develop, enabling innovation and accelerating time-to-market for new features.

Microservices allow engineering organizations to split services into small autonomous, functioning parts. Where companies used to construct a monolithic system architecture, nowadays they increasingly favor the idea of building self-contained services. This reduction in dependencies allows them to build faster, scale more easily, and maintain a continuous pace in innovation.

Our developer counterparts are increasingly adopting the mindset of microservices. While they hack away at their monolithic systems to break them up into manageable pieces, us designers still hold that single be-all and end-all design system as our holy grail.

With that in mind, I propose that we instead build our design systems to form a collection of individual, purpose-driven services. By mimicking the concept of microservices, our systems can build on top of one another and allow us to design faster. Likewise, they’ll be less dependent on a single point of failure.

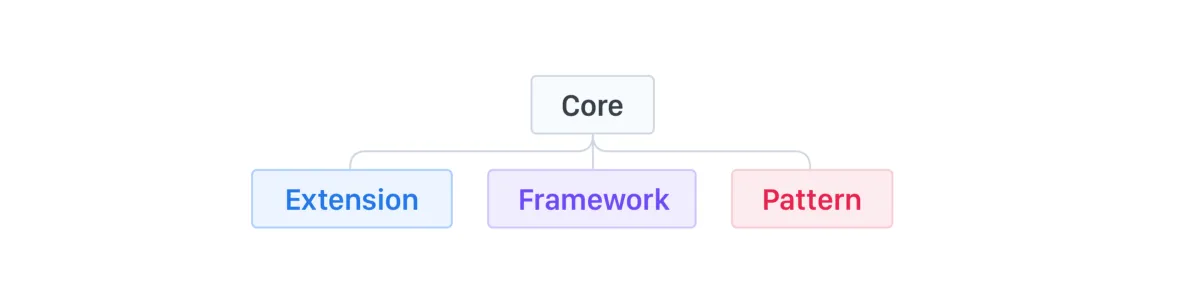

Breaking Up Our Systems

When modularizing our design systems, turning each part into a separate cog in a larger machine, it can be beneficial to categorize each of these services according to their purpose, origin, and degree of dependency on other services. By setting out with a clear definition of what makes up a certain type of service, it becomes easier to decide when to extract a service, rather than having to go through the painstaking process of extracting components later on.

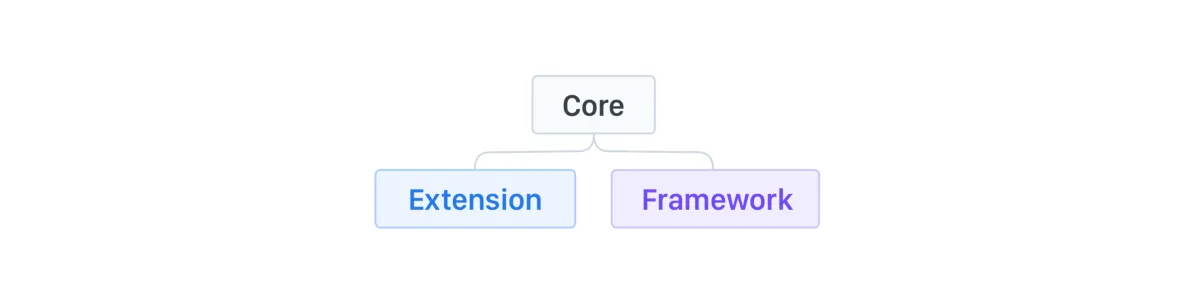

There are three service types that we can define from the get-go. These will likely spring up as our design system continues to grow.

- Core: The foundation of each design system.

- Extension: These services extend a particular element or set of elements in the Core service. They embed extra properties, often for a handful of specific use cases.

- Framework: Frameworks are purposeful services that can be reused across our products. They consist of several interrelated components.

At this stage, that still sounds rather vague. Let’s walk through each of the different service types one by one. Along the way, I’ll illustrate examples of the elements they can contain and how the services relate to one another.

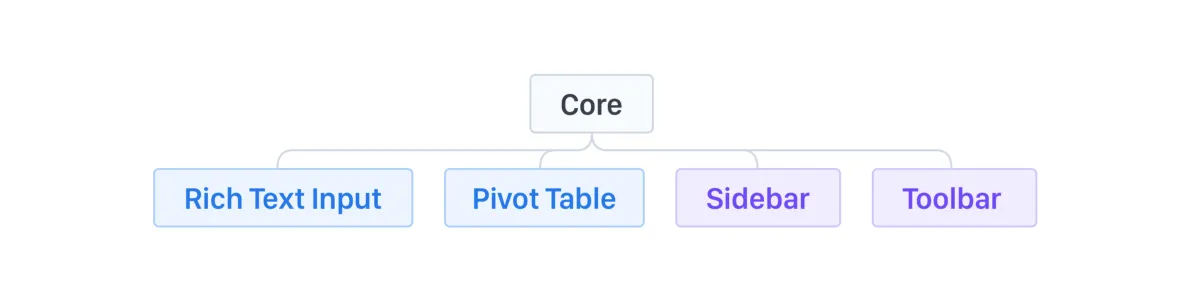

A strong core

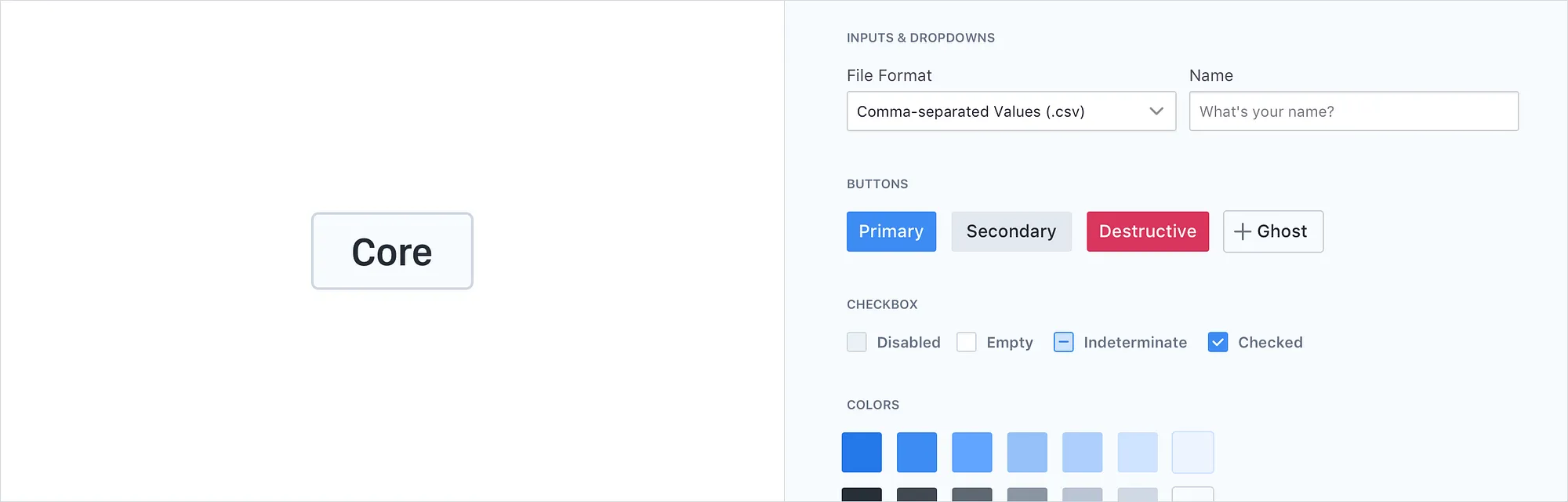

At the center of each design system sits a Core. This Core is where we start when mapping out use cases, defining their patterns, and laying the foundation of our products.

This is the service that every designer in the organization will contribute to, borrow from, and iterate on. Our Core houses foundational elements such as Color, Iconography, Spacing, and Typography. Additionally, we can define components here that stretch across the entirety of our products, components that will be used by every designer in every part of the product, such as Input, Checkbox, Button, or Dropdown.

As each designer will borrow from the Core, it’s vital that we establish and maintain a certain standard of quality. After all, any changes to these parts of our design system will likely affect every area of our product.

Note that Core is not a definitive naming convention. Call it whatever works for you and your team, be it Core, Foundation, Blueprint, etc. — as long as it’s clear that these form the fundamental, essential base layer of the product.

Core extensions

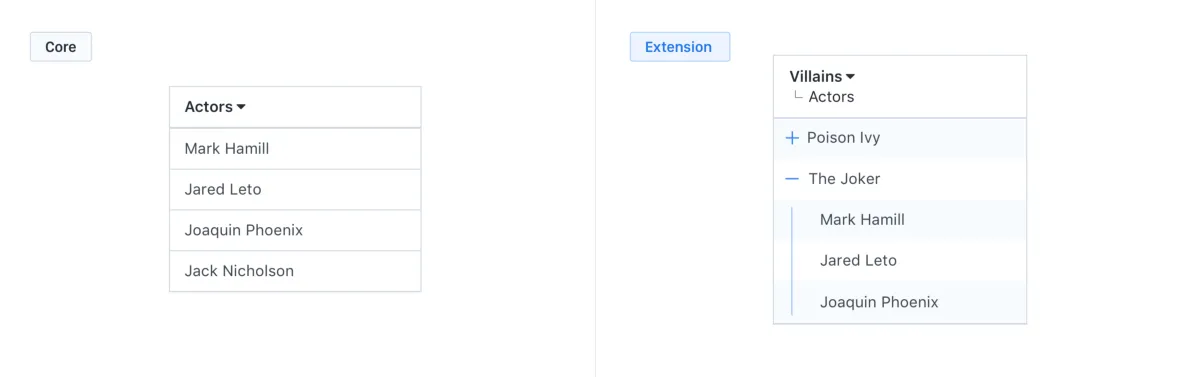

Extensions are services that borrow a component or a number of elements from our Core and extend their usage. By embedding additional properties, they enable us to utilize these components to address a different variety of use cases. These are often required to address complex issues in a specific context.

In the example above we see a Table consisting of a Table Header and multiple Table Cells. This simple table represents a handful of data points that exist on the same level. Its purpose is to visualize a categorized selection of data.

But what happens when we want to introduce more layers of complexity? What if we want to group the different data points or append more properties to our cells, such as Thumbnails? We’d need to extend the original header to display the different levels. And likewise, the cells should extend to contain the actions to expand or collapse data, as well as the lines indicating depth.

It’s likely that not every table in our product would need to display such complex levels of data. So if we were to insert each variation of a cell or table header in our existing Core, we’d quickly start bloating our design system. These components aren’t commonplace enough to constitute an essential part of our system.

Instead, we can extract these extended elements to a separate service. This allows us to iterate on the existing elements and build in additional properties that serve a specific purpose. All while maintaining a functional, minimal foundation.

Purpose-driven frameworks

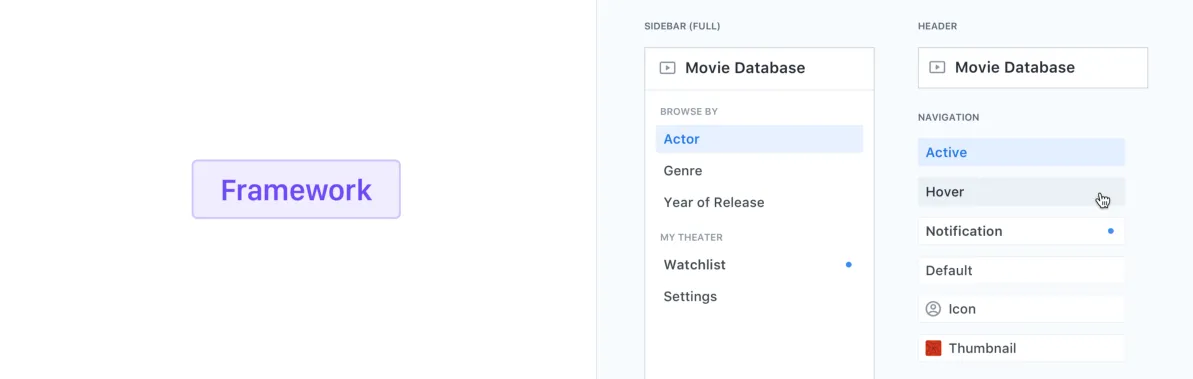

Frameworks do not rely or expand on existing foundational elements. Rather, they house a collection of elements that share a common purpose. Their main objective is to streamline the design process and enable quicker design iterations.

The example above demonstrates a Sidebar Framework. The sidebar in our example contains a handful of components used to construct it: A header indicating the general purpose of a page or product area, subsection headers to group content, and the different navigational components.

The different elements of the Framework are bound together by a common purpose. They don’t hold much significance on their own. Nor are they able to communicate their intent without relying on the entirety of the Framework. This sets them apart from the foundational elements in our Core. Components such as Buttons are able to communicate a specific function. We don’t need to rely on any other parts of our system to identify their purpose.

Extracting Frameworks has the benefit of keeping the Core light and agile. Framing these different elements makes it easier for any designer on our team to recognize what the intended function of an element is. This circumvents the need for convoluted naming conventions.

Whereas Extensions borrow from the existing elements and insert additional layers of complexity, Frameworks form a more complete, interconnected package from the get-go. Moving that to a separate service will thus result in a more immediate reduction in the number of moving parts in the Core.

A growing number of services

As our products develop, our design systems continue to expand in scale and scope. A monolithic approach can get unwieldy rather fast. Knowing that, we should aim to proactively extract different elements to a purposeful service.

In a perfect world, the number of different services will scale up parallel to our product development. Elements will flow at regular intervals between our foundational Core and the separate services, both upstream and downstream. Either we extract services the moment they grow so big that their size pollutes the foundation, or make a deliberate call to do so from the very start.

By moving elements into separate modules, we leave more room for experimentation. Whilst the Core maintains the highest standard due to its pervasive nature, the smaller, predefined scope of the other services opens up the ability to explore different variations.

Broadening the scope

At times we’ll come across various elements of our design systems that don’t fit the bill for either an Extension or a Framework. And that’s okay. The beauty of the proposed architecture is that there is room for expansion. Meaning we can add extra service types if we see a distinct need for them.

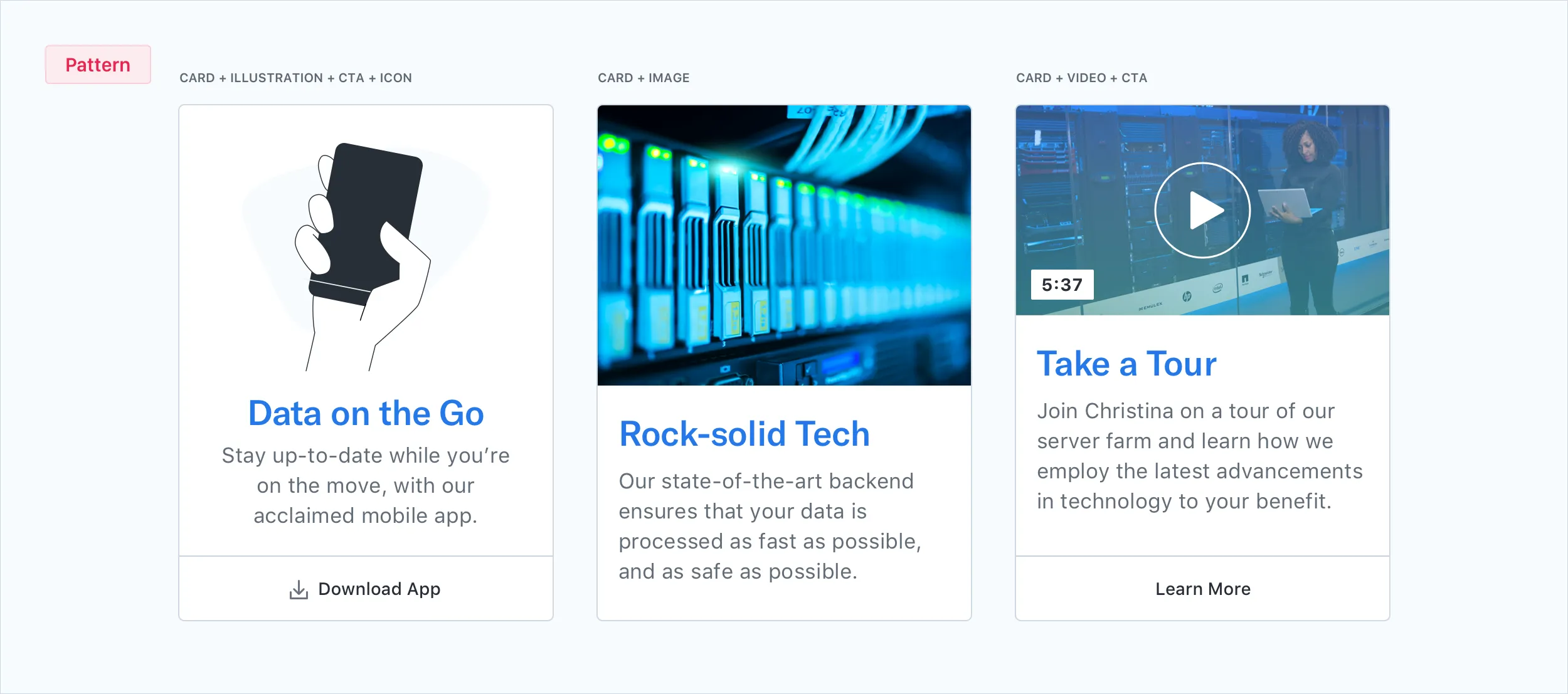

One such service type that we could come across is a Pattern. We’ve defined that Extensions build on top of existing components and add to their functionality. Likewise, Frameworks have a shared purpose. Patterns don’t exhibit either of these properties.

In the example above, there’s an instance of a Card Pattern. It’s composed of several elements that don’t adhere to either of the service types we defined earlier.

Cards are in essence containers for other elements. As seen in the three examples above, they can contain a large variety of different components, with little to no mandatory elements. The actual bare-bones Card — the combination of Background, Border, and Spacing — could very well be a foundational element.

The contents themselves aren’t bound together by a single shared purpose. Illustrations, photos, videos, and buttons can all appear in multiple places in our products. They can appear in different setups, with or without a Card to serve as a container. As such, Patterns are neither Extension nor Framework.

Rather, they serve as building blocks or guidelines. Their aim is to provide a frame of reference on how to lay out, combine, and piece together an interface of different parts. They’re templates that function as a starting point, rather than an end-to-end solution.

It’s easy, then, to see that as we continue to expand our design systems, we’ll come across use cases that are not categorized by the service types we set out with. And that’s exactly the point.

Our systems are no longer rigid, single-category monoliths. They are instead made up of different services that spring forth from the product development process. Different setups and companies necessitate different types and categorization. Defining service types beyond our initial set forces us to question our own classification and hierarchy.

Drawbacks

Like any approach, this too has its fair share of drawbacks. Many of the same issues that plague microservices also surface when building these micro design systems.

The biggest disadvantage of a microservices architecture is its increased complexity over a monolithic application. The complexity of a microservices-based application is directly correlated with the number of services involved. (Phil Wittmer, Tiempo Development)

Complexity is the main disadvantage for our systems, as well. A growing number of different services means that the responsibility for maintaining these services is spread out, rather than centralized. Additionally, it forces us to consciously extract existing elements out of our Core service. This means that we need to assign dedicated resources to do so.

While this is certainly a drawback, it also provides some benefits. Spreading out the responsibility of maintaining different services means less individual workload. It also enables us to enforce a higher level of quality on the Core, while keeping a degree of independence in the extracted services. This independence allows us to develop these extractions at a faster pace. We can thus innovate more rapidly and speed up feature development.

Luckily for us designers, recent developments in design tooling allow us to realize this approach in a rather efficient manner. Tools such as Figma support this model out of the box, by allowing users to plug-and-play different Libraries per project. We can thus easily assign different Extensions and Frameworks to projects as needed.

Another drawback is that micro design systems are not true microservices. Whereas microservices exhibit complete autonomy, our design systems still rely on a certain degree of interconnectivity. Extensions still borrow from the Core service, and our features still rely on several degrees of connectivity. These connections are unlikely to go away at any point in the future. The nature of design work — and front-end development for that matter — is intrinsically bound by this.

As a counterpoint, these relationships between elements also enforce a distinct degree of visual consistency. Any given interface is likely to consist of several elements, borrowing from different services. Having these services be visually different would then become immediately clear.

With many of our design systems still in their infancy, now is the time for us to mature our work. By modeling, categorizing, and extracting the different services in our systems, we force ourselves to answer questions about the nature of different elements, set quality standards for their foundation, and prepare them for the future.

Our tools are already paving the way for us to change the way we think about our work. Following in their footsteps will allow us to establish a shared language and improve our design systems for the better.